One year on … can we see a turning point for Venezuela?

One year ago, there was hope that the social and economic decay in

Venezuela could be stopped. And that it wouldn’t be too long until a political solution could bring the country back to democracy.

It didn’t turn out that way.

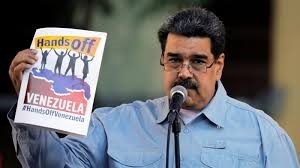

Instead, President Maduro’s position appeared strengthened during last

year, after the failed attempt by the opposition to bring the military to

change side. Juan Guiadó, president of the National Assembly, which was legitimately elected in 2015, has not reached his pronounced goal of regime change. His standing in public opinion has gradually become weaker.

The negotiations between the regime and the opposition on a way towards democratic elections, with Norwegian diplomats as mediators, got stuck in the beginning of the fall. The regime left the table, after the US had imposed broader sanctions on Venezuela.

During the fall, the regime entered an agreement with some smaller

opposition parties, thereby succeeding in dividing the opposition. In the

beginning of this year a cooperative deputy was elected, under coup-like conditions, as president of the National Assembly. Guaidó and the deputies supporting him were physically prevented from participating. The parliament is now divided in two parts, one led by Guaidó and one more inclined to collaborate with the regime.

The regime gets political and material support from some other authoritarian governments, above all Russia and Cuba. As the re-election of Maduro in 2018 has been branded as undemocratic, Guaidó is recognized as interim president by several countries, including USA. He is supported by even more, among them neighboring countries in Latin America, EU and Sweden, in his position as president of the democratically elected National Assembly.

At the same time, the general situation for the country and the population has deteriorated further.

Imprisonments without trial and harassment of opposition figures continue.

The economic downhill slope is steep. Even though various products are again available in the shops in Caracas, if you can pay with dollars, most of the population lives under the poverty limit. A large portion is malnourished and there is shortage of fuels. It is estimated that around 4.5 million people, of the approx. 30 million inhabitants, have left the country. The exodus continues, at the tune of 4 000 – 5 000 persons per day.

Venezuela’s oil production, the backbone of the economy, has decreased with 80 per cent since the peak around year 2000. The largest part of this collapse has happened since the high oil prices fell back in 2014 and since Maduro became president. Venezuela has had shrinking volumes of oil to export at market price – much has been delivered with a discount or as repayment of loans from Russian companies and from China. During the last years, the gradually tightened sanctions from the US have rendered exports more difficult.

Going from bad to worse, the oil prices have fallen, since the beginning

of March, to their lowest level in 20 years. This is a result of the price war between Saudi Arabia and Russia, and of the declining demand due to the Covid-19 pandemic.

This pandemic now also casts its shadow over Venezuela. The deficient

health system, lacking all sorts of supplies, will have limited capacity to

care for a growing number of sick people.

Although it can seem like the regime has increased its possibilities to

survive, its ability to fight the humanitarian, economic and health related

crises is weak.

So, how can the country escape this desperate situation?

The regime is not inclined to voluntarily put its position at risk in

free elections. The opposition, on their part, has not been able to unite on the course forward. The military is careful and avoids taking risks. The prospects are slim, as I see it, that the political forces in Venezuela on their own will be able to agree on solutions to the enormous problems. Active engagement by the international community is needed.

The stream of refugees, the shortage of food and drugs, and the approaching pandemic make aid from the outside necessary. For economic growth in the longer perspective, the petroleum industry must be rebuilt. That task will also require international participation, financially and technically.

The democratic crisis can only be solved through free and fair elections.

Conditions do not exist for such elections as long as Maduro has unlimited power. An agreement on a transitional government, with participation of different political forces and support from the military, is the way that moderates in the opposition and many foreign friends of Venezuela have advocated for a long time.

On March 31st, Secretary of State Pompeo launched a plan in this direction: ”Democratic Transition Framework for Venezuela”. According to the plan, the constitutional role of the National Assembly shall be restored, and political prisoners be freed. A Council of State of five persons, representing the main political factions, shall be elected and assume the executive power. Free elections of parliament and president shall be held within 6 – 12 months. The military high command stays in their positions. An international program for humanitarian and economic aid will launched.

If the plan is followed, the US and EU will gradually lift sanctions on

those who are in power and on the sale of oil; when correct elections have been held all sanctions will be discontinued.

The plan builds on the discussions last summer, under Norwegian guidance. It seems that USA now clearly backs a diplomatic solution, agreed between the Venezuelan parties. Can this be the point of departure for a new start for Venezuela? The plan requires that Maduro steps aside, but he doesn’t have to leave the country and he and his circle will be free from the sanctions. Neither will Guaidó lead the country, the executive power, until elections, will be held by the Council of State, where no member can be a deputy of the National Assembly.

A few days earlier the American Department of Justice had indicted Maduro and a few other, central regime figures for narcotrafficking and put a big ransom on his head. This action gives the impression of a rather uncoordinated US policy. For "the transition framework" to succeed, the US must surely be prepared to withdraw the indictment and the threat of extradition. If not, the regime gets an extra reason to cling to power.

The first reaction from the regime in Caracas was, as could be expected,

to reject the American transition plan. Our country is sovereign, one said, and will not submit to dictates from foreign powers. But this sovereignty is rather hollow. Cooperation with the international community is the only way out of the crisis.

The position of Russia will be important. It would be an important signal

if Russia chooses not to stand in the way for a negotiated process along the lines of the American plan. A few days ago, the largest Russian investor in Venezuela, the oil company Rosneft, announced that they will leave Venezuela and transfer their interests to an unknown, state-owned company. That could be a maneuver to avoid the American sanctions, but it could also be a sign that the support for Maduro is wavering.

In the end it will probably be the attitudes of key people in Maduro’s circle and in the military leadership that will determine the outcome.

The crises in Venezuela have deepened during the year past. In the best

case, we may now see a turning point.